The Anioma Story of Resilience

See the courage, struggles, and legacy of the Anioma people through key historical events.

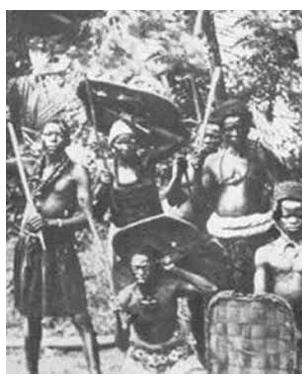

Ekumeku War – Anioma’s Defiant Struggle Against Colonial Domination

The Ekumeku War (c. 1883–1914) stands as one of the longest and most determined resistance movements against British colonial expansion in southern Nigeria, with Anioma communities at its heart. Rooted in the Delta North region, Anioma towns such as Ibusa, Ogwashi-Uku, Owa, and Asaba faced severe economic and political disruptions as the Royal Niger Company monopolized trade, particularly palm oil, undermining local autonomy and exploiting the people. In response, young Anioma men organized a secret resistance movement known as the Ekumeku, committed to defending their lands, livelihoods, and identity.

The movement was highly disciplined, relying on guerrilla tactics, intimate knowledge of the terrain, and strict secrecy, which earned it both fear and respect from colonial forces. The name “Ekumeku” is rooted in Igbo: “Aya Ekumeku” or “Aya oyibo” — “war” against foreigners — while “Ekwumekwu” roughly translates to “do not talk about it,” indicating the secrecy, stealth and guerrilla nature of the insurgency. Over the course of three decades, the Ekumeku engaged in numerous confrontations with the British, including punitive expeditions against Ibusa in 1898, fierce resistance in Owa in 1904, and the Battle of Ogwashi-Uku in 1909. Despite being poorly armed compared to the technologically superior colonizers, the Ekumeku fighters inflicted significant losses, delaying full British control and demonstrating remarkable strategic and organizational skill. Beyond military resistance, the war showcased the political consciousness and unity of Anioma people, showing that they were not passive bystanders but active defenders of their autonomy. The significance of the Ekumeku War extends beyond local resistance. It reflected the Anioma people’s political awareness, unity, and refusal to bow to foreign domination. It also firmly places Anioma within the Igbo cultural and political story, proving that they have always been active participants in shaping the affairs of the Southeast. Today, the Ekumeku War stands as a proud reminder of Anioma resilience, a legacy of courage, leadership, and commitment to justice.

Anioma Military Leaders in the Biafran Army

Anioma played a significant role in the Nigerian Civil War (1967–1970), producing a number of notable military officers who served in the Biafran Army. Among the most prominent was Major Chukwuma Kaduna Nzeogwu, whose parents hailed from Okpanam. Although Nzeogwu was born in Kaduna, his Anioma roots placed him within the Igbo-speaking communities of Delta North. He was a central figure in Nigeria’s first military coup on 15 January 1966. Following the coup, anti-Igbo pogroms in northern Nigeria and attacks on Anioma communities demonstrated how deeply the region was affected even before full-scale war erupted.

Other notable Anioma military leaders in the Biafran Army include:

- Colonel Azum Asoya: Rose to become one of the youngest General Officers Commanding (GOC) in the Biafran Army.

- Colonel Mike Okwechime: A divisional commander, appointed Adjutant-General and Chief of Logistics at the Biafran Defence Headquarters.

- Brigadier Conrad Dibia Nwawo: Initially commander of the Nigerian Army’s 4th Area Command in the Mid-West, later commanded Biafran 11th and 13th Divisions.

- Colonel Joseph “Hannibal” Achuzia: Known for tactical skill, led the Biafran 16th Division.

- Brigadier Sylvanus Nwajei: Senior military officer who returned home to take up arms for Biafra.

- Brigadier Nduka Okwechime: Served as Army Adjutant-General.

- Professor Chukwuka Okonjo: Father of Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, served as a brigadier in the Biafran Army.

Anioma Massacres During the Nigerian Civil War (1967–1970)

During the Nigerian Civil War, the Anioma people, located in what is today Delta North Senatorial District, suffered some of the most brutal reprisals of the conflict. Their tragedy stemmed not from any collective act of rebellion, but from their linguistic, cultural, and historical ties to the Igbo ethnic group. Although politically situated in the Mid-West (now Delta State), Anioma communities have always shared deep sociocultural connections with the Igbo people of the South East. Their language, traditional titles, festivals, and kinship systems all reflect this shared heritage. It was this identity that tragically marked them during the war years.

The Asaba Massacre – October 1967

As retreating Biafran forces passed through Asaba, federal troops entered the town and accused the people of harboring or supporting the rebels. In an effort to prove their innocence and loyalty to Nigeria, the townspeople, men, women, and children, gathered peacefully at Ogbe-Osowa Square on 7 October 1967, dressed in akwa ocha (white cloth), a symbol of peace, and chanting “One Nigeria.” The soldiers opened fire on the unarmed crowd, killing more than 700 civilians in cold blood. The Asaba Massacre stands as one of the most documented mass killings of the Civil War.

The Isheagu Massacre – 1968

Around the same period, Isheagu in Aniocha South also became a target. Federal troops, labeling the community as “Igbo sympathizers,” descended on the town with unspeakable brutality. Eyewitnesses recall how entire families were wiped out. Community elders, including the Okpala Uku (traditional ruler), were executed. Women, children, and pregnant mothers were not spared. Over 600 civilians lost their lives. In some accounts, the king was reportedly buried alive, and pregnant women were gruesomely killed, acts that shocked even hardened observers of war.

A Shared Identity, A Shared Suffering

The Anioma people were not attacked for what they did, but for who they were. Their Igbo identity, expressed in language, culture, and kinship, made them targets in a war that blurred the line between the political and the ethnic. In Asaba, 700 men and boys were executed in a single day. In Isheagu, over 600 civilians were slaughtered, including elders and community leaders. These events remain a permanent scar and solemn reminder that the Anioma people’s place in history is inseparable from the wider Igbo experience, in dignity, in suffering, and in resilience.