Discover the rich linguistic heritage, cultural traditions, and historical roots of the Anioma people.

The people of Anioma trace their origins to different waves of migration. From Arochukwu traders of the old Eastern region, to migrants from Benin and Igala. Yet, among all these connections, the cultural and linguistic bond with the Igbo stands out as the strongest and most enduring.

The Anioma speak dialects such as Enuani (Aniocha/Oshimili), Ika (Ika North East/South), and Ukwuani-Aboh-Ndoni (Ndokwa/Ukwuani), all closely related and easily understood among themselves and their kinsmen across the Niger. The names of these subgroups reflect both geography and history: Enu-Enyi meaning “our upland dwellers,” Ukwuani for “walkers on land,” and Ndosumili describing “people of the river.”

Together, they embody a blend of upland and riverine Igbo civilization, distinct in expression but united in cultural essence. Festivals, proverbs, chieftaincy systems, and communal values across Anioma mirror those of their brothers and sisters in the South East. During the Civil War, Anioma people were identified and targeted as Igbo, a painful reminder of how deeply intertwined these identities have always been. Today, the prospect of Anioma being grouped with the South East is a welcome and historic development, reuniting the region with the ancestral roots from which many of its forebears migrated to found the land now proudly called Anioma (“the good land”).

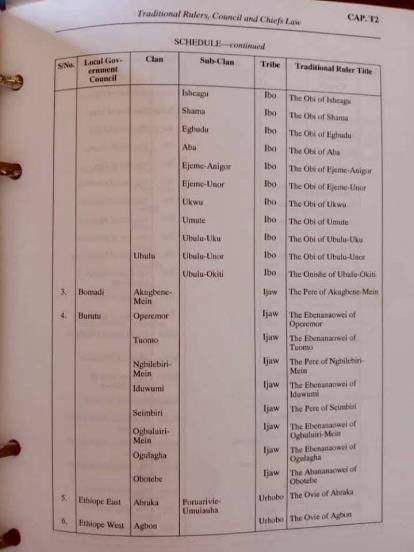

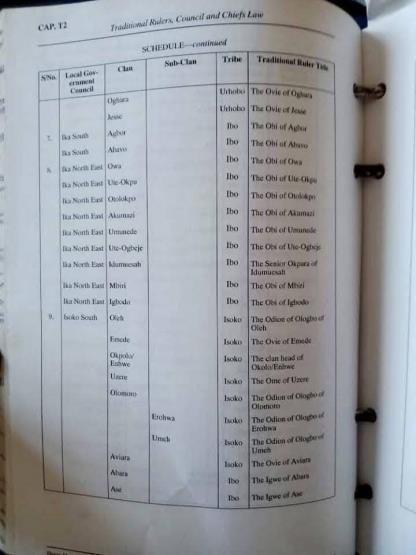

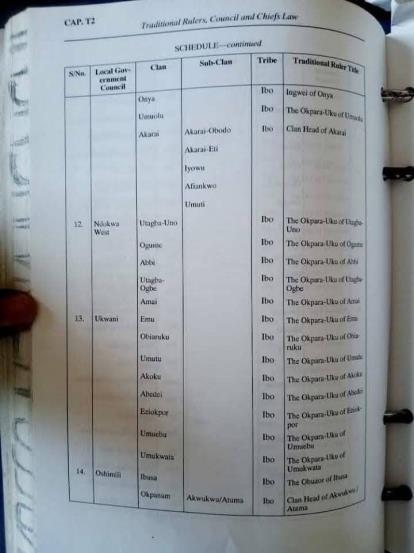

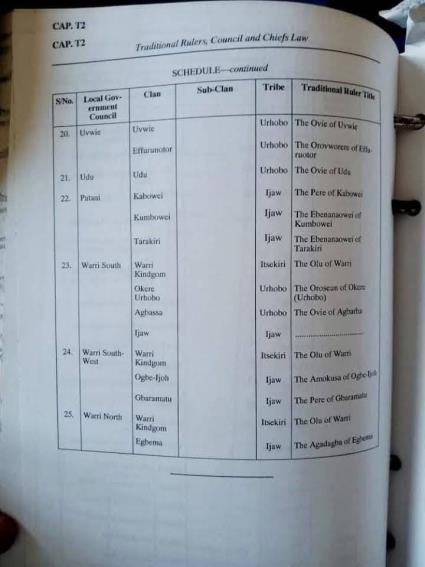

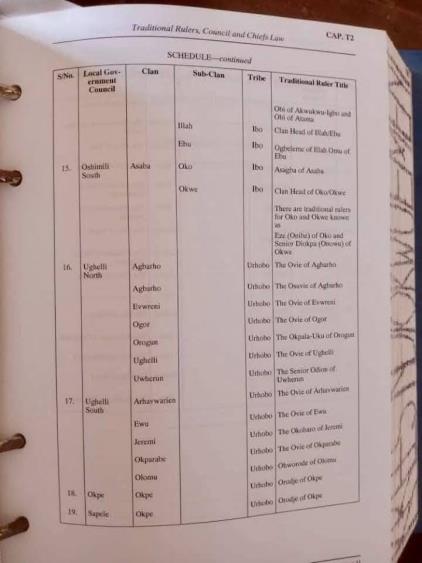

During the era of House of Chiefs, Anioma people were referred to as Western Igbos. Later when the Midwest was mapped, we were then referred to as Midwest Igbos. After that, Aniomas were mapped together with Edo and Delta as one which is Bendel. While with Bendel, Aniomas were called Bendel Igbos. And then it trickled down to the creation of Delta State and Aniomas are today called Delta Igbos. History overtime acknowledges that Aniomas are Igbos. In contemporary times, Delta state, where the Anioma people currently share with other ethnicities, officially recognizes only 5 ethnic groups within the state. These 5 ethnic groups are Igbo (Enuani, Ika & Ukwuani), Urhobo, Isoko, Itsekiri & Ijaw. The Aniomas are the Igbos. Though we speak in varied tongues or dialects, we remain bound together by common kinship ties, culture, traditional belief systems, festivals, and enduring communal values.

Governance and social order in Anioma are anchored in a rich system of traditional leadership. From the Obis and Ndiches to our community elders and cultural councils, we maintain respected institutions that preserve justice, mediate disputes, and uphold customs that define our shared experience. These monarchical structures remain vital in maintaining social cohesion and fostering unity across communities, serving as a spiritual and cultural backbone that links our past with our future.

Historically, we existed as autonomous but interrelated clans, self-governing, economically integrated, and culturally intertwined. Our ancestors thrived through farming, fishing, and trade. The arrival of colonialism, however, altered this natural order. For administrative ease, the British split our ancestral territory, placing the Aboh Division in the Warri Province and the Asaba Division in the Benin Province despite our obvious internal coherence. This balkanization weakened our administrative unity, but not our sense of belonging. Our communal relationships sustained through intermarriage, trade, religion, and shared histories remained unbroken, forming the durable social fabric that still binds us today.

We, the Anioma people, occupy a geographically strategic corridor in southern Nigeria. We are bounded to the east by Anambra and Rivers States, to the south by Ethiope East, Ughelli North, Isoko North and South, and to the north and west by Edo State. The River Niger, which runs along our eastern flank, connects us naturally to the rest of the Niger Delta, making Anioma not only a land bridge but also one of the coastal states of the Niger Delta. This location gives us significant access to inland and coastal resources and opportunities.

As part of the larger Western Region during the pre-independence era, our communities played pivotal roles in Nigeria’s educational and political development. Our leaders and thinkers were at the forefront of regional governance and national advancement. The influence of our people stretched from the Western Region’s boundaries as far west as Dahomey, north to Katunga in present-day Niger State, east to Asaba, and south to the Atlantic Ocean. Even after colonial incursion redrew these boundaries, our contributions to regional progress and national identity remained evident.

In the face of colonial oppression, we also stood firm. The Ekumeku movement, one of the longest anti-colonial resistance campaigns in southern Nigeria, was born out of our unified opposition to the divisive tactics of colonial rule. Our people from both the Aboh and Asaba divisions fought side by side, demonstrating the unity and resilience that continue to define us.

Our local economy remains rooted in agriculture and fishing. We cultivate cassava, yam, maize, rice, and palm produce, while our riverine communities are skilled in inland fishing. In modern times, we have also embraced trade, education, enterprise, and professional advancement. Our towns are home to thriving markets, skilled artisans, vibrant schools, and increasing infrastructure. Communities like Asaba, Agbor, Kwale, Ogwashi-Uku, Aboh, and Issele-Uku are not just traditional towns, they are growing urban centers of commerce, governance, and learning.

Modern-day Anioma is also home to thousands of non-indigenes who have settled in the region over the years, drawn by its welcoming environment, social harmony, and economic opportunities. This inclusiveness continues to define the Anioma spirit. One that is forward-looking, respectful of tradition, and open to collaboration.

While each Anioma community has its unique history and nuance, together they reflect a cultural synthesis that has evolved over centuries. A mosaic shaped by local customs, external influences, and shared experiences. This collective identity has become even more pronounced in the face of modern governance and development challenges, reinforcing the belief among Anioma people that statehood is the logical next step in our historical journey.